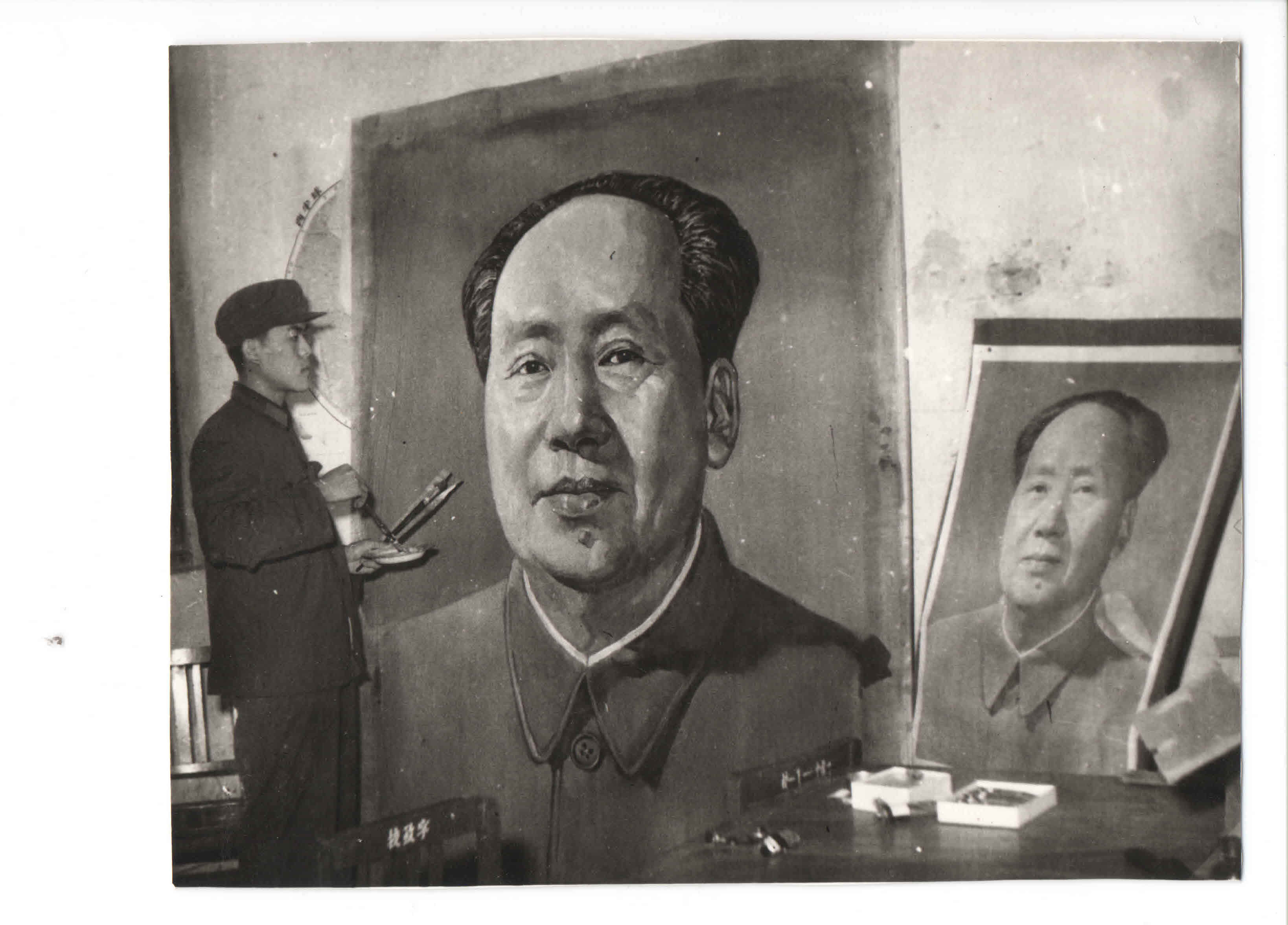

In September 1976, Li Shaomin was called to the office. He was informed about the death of Chairman Mao and was ordered to paint a black and white portrait of the Chairman for the local funeral ceremony. "I immediately framed the canvas, about two metres in length and height, and start painting. I only used one day to finish it," said Prof Li. The then 17-year-old boy never expected that years later he would hold a solo exhibition about Chinese contemporary art at the Chrysler Museum of Art.

▲Li Shaomin painting a black and white portrait of the Chairman, Shijiazhuang, China, 1976. Photograph Bi Wenchen

Today, Li Shaomin is a professor and eminent scholar at Old Dominion University in the United States. He has collected Chinese propaganda artworks for more than 10 years. In recent years, Chinese propaganda art has become popular in the global art market. Liu Chunhua's Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan sold for more than 6m yuan ($800,000) at the China Guardian Auctions in 1995. In 2009, Shen Jiawei's Standing Guard for Our Great Motherland hammered down for 7m yuan ($1m). Last year, The Whole Country is Red sold for 13m yuan ($1.9m), becoming the most expensive stamp in the world.

Moreover, many private museums in China are fond of propaganda art. Wang Wei, the founder of the Long Museum, is one of the most famous Chinese propaganda art collectors. The Long Museum has held several exhibitions under the theme of "Red Art" in the last few years.

▲Feature exhibition of Standing Guard for Our Great Motherland at Long Museum in Shanghai

Nevertheless, the value of Chinese propaganda art is merely hype. Most Chinese propaganda artwork currently in the market are low-quality original prints. The main sale channels are antique shops and online platforms. These artworks generally sell for no more than 10,000 yuan ($1,500).

There's no denying that when it comes to art value, Chinese propaganda art is worth little. When the West was experimenting with cubism, abstractionism, and symbolism, Chinese propaganda art was still focused on "making it looks real". Additionally, most of the propaganda art in China imitated works from the Soviet Union and Poland.

Furthermore, since all propaganda art poster ideas were assigned to painters, it is hard to see any creativity or individualism in these paintings. Prof Li explained his own experience as a propaganda art painter: "Our paintings were always about government policy or ideological education. We could always find a template to copy. There's nothing new in them.”

However, from a historical perspective, propaganda art represents an important part of Chinese history.

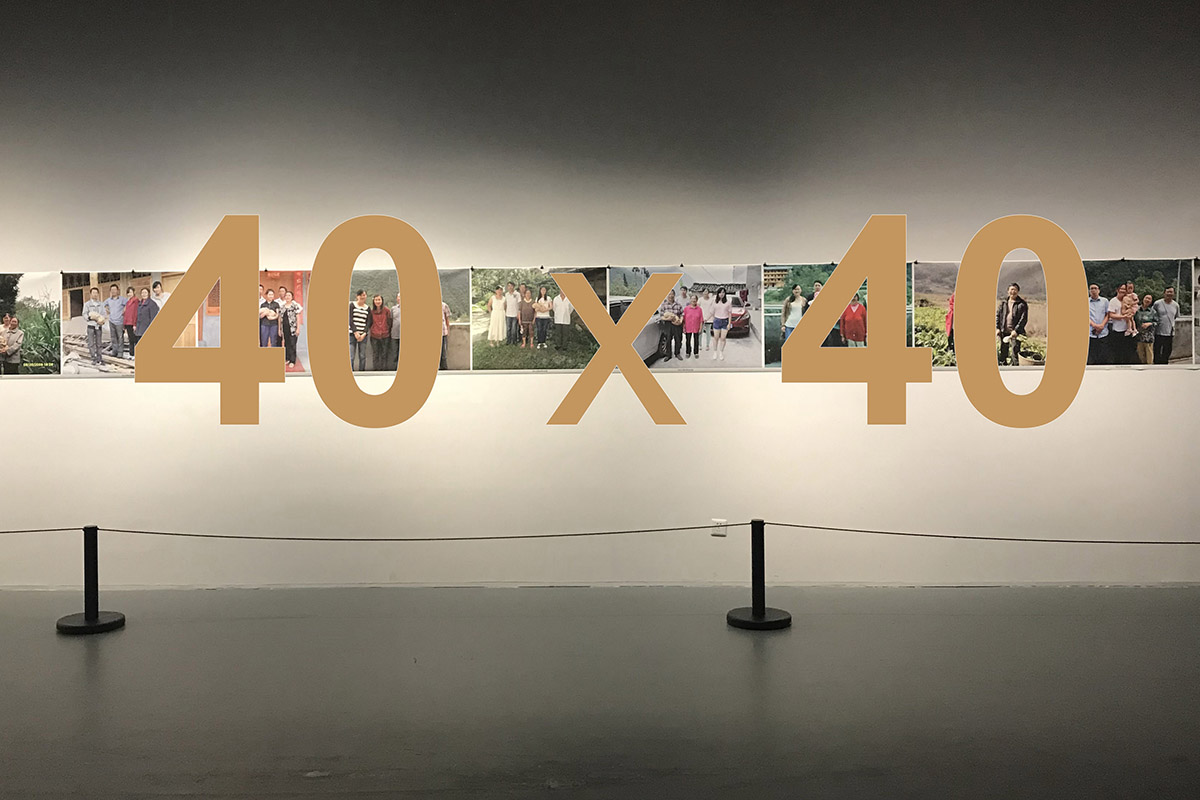

▲Li Shaomin's solo exhibition about Chinese contemporary art at the Chrysler Museum of Art

Propaganda art first appeared in China in the 1930s. It was used to encourage the spirit of the country during the Sino-Japanese War. Due to a lack of resources, most works from that time are woodblock prints. Even in poor condition, a print can sell for more than $100,000 in the market nowadays.

After the establishment of the People's Republic of China, propaganda art became the mainstream. As many people were illiterate in the new China, propaganda art was used to easily promote government policy. According to research by Chen Lvshen, the former curator of the National Museum of China, the Chinese government printed 16 million propaganda posters between 1958 and 1959. The number of the prints produced in the past 8 years is the same amount as those produced in 1959 alone.

The climax of Chinese propaganda art production was during the Cultural Revolution. Propaganda posters created during that time are the most recognised in the world today. Presented in black, white and red, portraits of Chairman Mao's profile and military motif, make up the propaganda art from the 1960s. Prof Li said: "It was easy to draw a portrait of Chairman Mao because that's what we did every day as a propaganda art painter. In fact, everyone was drawing Chairman Mao at that time.”In the 60s, the painting Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan was copied into about 100 million prints.

▲Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan

However, what's left of the artwork now?

Among the top 10 travel destinations in Shanghai on TripAdvisor is a basement at the President Mansion in the former French Concession. This is the Propaganda Poster Art Centre, a museum dedicated to Chinese propaganda posters created during the 1920s to 1960s. For many foreigners, this is the place that satisfies their curiosity about Communist China.

Ironically, the art centre is unknown to many local residents.

▲ Propaganda Poster Art Centre in the former French Concession

Famous Chinese artist Chen Danqing once said in a BBC interview: “In the western concept of contemporary art, ‘motif and symbol’ are the two most important things. However, there aren’t many Chinese symbols or motifs well-understood by the West except few like Chairman Mao. It is doomed to be consumed by the West.”

This may explain why 90% of the visitors at the Propaganda Poster Art Centre are Westerners, and why artworks that contain Chairman Mao always sell better in the antique shops as Prof Li told us. Furthermore, the fondness of Chinese propaganda art by the West can be seen as political satire towards China as Prof Huang Heqing from Zhe Jiang University explained during an interview with BBC.

However, for many academic institutions in the West, Chinese propaganda artworks are important documents for studying the history of the Cultural Revolution. The British Museum has collected nearly 90 Chinese propaganda art posters. The University of Westminster has established the Chinese Poster Collection and collected more than 800 propaganda artworks.

On the other hand, for many Chinese people like Prof Li, Chinese propaganda art represents the time they were living in. Prof Li explained: “The reason why I like propaganda art is that I was living in that time. I have a special bond with the art. However, it doesn’t mean Chinese propaganda art is important in the art history.”

Valuable or not, Chinese propaganda art is a representative of 20th Century China. Chinese politics may drastically change over generations, but the art and its history, important or not, remains.